Last Saturday, July 4, a group of Malaysians known as the Advocates of the Propagation of Science Literacy (APOSL), decided to celebrate the life and scientific contributions of Dr Rosalind Franklin. It was also the group’s third anniversary.

Personally, I figured that celebrating the person infamously known as the Dark Lady of DNA and focusing on the good of science would take my mind off the humdrum of recent Malaysian news.

Personally, I figured that celebrating the person infamously known as the Dark Lady of DNA and focusing on the good of science would take my mind off the humdrum of recent Malaysian news.

The escalating cost of living due to the GST as well as the rigorously reported, worrying scandal involving 1MDB in the background made me feel hopeless that I crave a distraction and refreshed motivation.

Further, the screening of documentaries on Rosalind Franklin was followed by a buka puasa attended by APOSL members of all ethnic backgrounds and religions, a testament to point that what unites Malaysians would always be food.

Rosalind Franklin was born on July 25, 1920 to an upper middle-class, religiously conservative English-Jewish family.

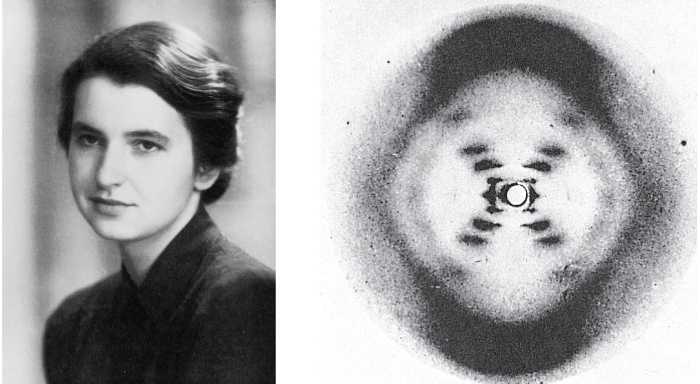

Dr Rosalind Franklin, infamously known as the Dark Lady of DNA, and the X-ray diffraction Photo 51. – http://bio1151.nicerweb.com pic, July 8, 2015.Her upbringing was described as privileged, and her passion for the sciences cultivated from her desire to be irreligious.

Dr Rosalind Franklin, infamously known as the Dark Lady of DNA, and the X-ray diffraction Photo 51. – http://bio1151.nicerweb.com pic, July 8, 2015.Her upbringing was described as privileged, and her passion for the sciences cultivated from her desire to be irreligious.

In a letter to her father, Rosalind wrote, “You look at science (or at least talk of it) as some sort of demoralising invention of man, something apart from real life, and which must be cautiously guarded and kept separate from everyday existence. But science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.”

Rosalind became one of the few women accepted into the prestigious Cambridge University on scholarship, and pursued her passion in physics and chemistry despite the disapproval from her parents on her career choice.

It was during her undergraduate years, with World War 2 the background, that she learnt the X-ray diffraction technique that would one day become both her biggest achievement and failure.

Rosalind did not let the war affect her science. Her contributions to the war efforts was on improving gas masks, a wartime device that went on to save many lives in air-raid affected Britain then, through her work on the porosity of coals.

That particular work also became part of her PhD thesis, “The physical chemistry of solid organic colloids with special reference to coal”, and she was awarded a PhD from Cambridge in 1945.

Rosalind then left for Paris, after being accepted into Laboratoire Central as a researcher. She perfected her X-ray diffraction technique during her time in Paris, and enjoyed her time in a laboratory that allowed her to grow as a scientist and a balance on enjoying the life she had in the city.

Due to the nature of their work, Rosalind and members of her laboratory were frequently checked for overexposure to X-ray, and they would be asked to stay away from the lab if they were found to have above average levels of X-ray.

Rosalind would be upset when she had to leave the laboratory, as that would cost her time to complete her work.

Rosalind then worked at King’s College, where a miscommunication occurred with regard to her position.

To her, she was supposed to be an independent researcher, but to Maurice Wilkins, another scientist also working on DNA, she was supposed to be his assistant.

This patriarchal view, that a woman is not a scientist that is of the same level as her colleagues, was rampant in King’s College, and even England at the time.

Wilkins went on to collaborate with Francis Crick and James Watson from Cambridge University, two scientists who aimed to solve the DNA structure by building models.

Evidently, Watson came up with the conclusion on the model for the double helix structure after seeing Rosalind’s Photo 51, the clearest X-ray diffraction photo taken of DNA in its B form.

The resulting compromise was for Watson and Crick to publish the model in Nature, and for Rosalind’s paper on the X-ray photograph to support the proposed model.

Unhappy with her time at King’s, and of the treatment she received in the race towards revealing the structure of DNA, Rosalind left to work at Birkbeck College and collaborated with Aaron Klug, another Nobel Laureate-to-be at the time.

It was during her time at Birkbeck that she excelled in her science and became an acclaimed virologist.

Rosalind was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in mid-1956. She continued to work but eventually succumbed to the illness on April 16, 1958.

Exposure to X-ray radiation is sometimes associated to cancer, and it must not be discounted in her case. The Nobel Prize for the discovering the structure of DNA was awarded in 1962, to Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins. The Nobel could not be awarded posthumously, thus, Rosalind Franklin’s name is relegated to a footnote in history.

It is only recently that Rosalind Franklin’s name is extracted from the archives of scientific history. A university in Chicago was recently named after her, with Photo 51 used as their university emblem.

In a world where women are often still considered unequal to men, especially in male-dominant fields, the feminism behind the story of the Dark Lady of DNA, is imminent and one that should continue to inspire.

Personally, Rosalind’s story was a story of dedication, passion, and perseverance. There is no use for acclaim and fame, if one cannot deliver. It keeps me humble and will continue to inspire me for years to come. – July 8, 2015.

* The columnist chose to use Rosalind’s first name to highlight the gender disparity in this story. Main resource for this article is the book “Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA” by Brenda Maddox.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of The Malaysian Insider.

Comments

Please refrain from nicknames or comments of a racist, sexist, personal, vulgar or derogatory nature, or you may risk being blocked from commenting in our website. We encourage commenters to use their real names as their username. As comments are moderated, they may not appear immediately or even on the same day you posted them. We also reserve the right to delete off-topic comments